Hospice Care 101

What Is Hospice?

Hospice is not about giving up. It’s about living fully and with dignity when facing a life-limiting illness. At its heart, hospice care is a philosophy: every person deserves comfort, compassion, and support in life’s final chapter.

A Different Kind of Care

Where traditional medicine often focuses on curing disease, hospice focuses on quality of life. Hospice teams relieve pain, manage symptoms, and provide emotional and spiritual support for both patients and families. It is care designed around the whole person—not just their illness.

Who Provides Hospice Care?

Hospice is a team effort. Physicians, nurses, aides, social workers, chaplains, counselors, and trained volunteers work together to:

Control pain and symptoms so people can live as comfortably as possible.

Offer emotional and spiritual support that respects every belief and value.

Guide families through decisions, grief, and the challenges of caregiving.

Where Hospice Happens

Hospice care is flexible and comes to where you are most comfortable: in your home, a nursing facility, an assisted living community, a hospital, or an inpatient hospice center. The goal is always the same—comfort, dignity, and peace of mind.

Who Is Hospice For?

Hospice is for anyone with a life-limiting illness—not just those with cancer. Heart and lung disease, dementia, kidney failure, neurological conditions, and many other illnesses may qualify. Hospice begins when treatment is no longer helping or when a person chooses to focus on comfort instead of cure. Importantly, hospice is not just for the last days of life—many people and families benefit from months of care and support.

Why Hospice Matters

Hospice affirms that while medicine may not always cure, it can always care. It helps patients live with purpose and comfort, while surrounding families with guidance and support. Hospice allows people to spend less time in hospitals and more time where they belong—with loved ones.

The Heart of Hospice

Hospice is about more life in the time that remains. It is about listening, honoring choices, and providing the tools and support to walk this journey together. At HEN, we believe hospice is not the end of the story—it’s a way to ensure the final chapter is written with comfort, dignity, and love.

Hospice through the years

From ancient waystations for weary travelers to a global healthcare movement, hospice has always been about one thing: caring for people with compassion and dignity at the end of life. It reminds us that while medicine may not always cure, it can always comfort.

-

The idea of caring for the dying with compassion is far older than the modern hospice movement. In ancient cultures, including Greek, Roman, and early Christian communities, hospitality and care for the sick and dying were considered moral duties.

Middle Ages (11th century): The word hospice comes from the Latin hospitium, meaning both “guest house” and “hospitality.” Religious orders—most notably the Knights Hospitaller—founded waystations along pilgrimage routes in Europe to provide rest and care for travelers, the sick, and the dying. These “hospices” were places of shelter, dignity, and comfort.

-

As medicine advanced in the 17th–19th centuries, hospitals became increasingly focused on curing disease. Care for the dying was often neglected, leaving families, religious orders, or charity houses to provide comfort.

1842: The Irish Sisters of Charity opened Our Lady’s Hospice in Dublin, one of the earliest institutions explicitly devoted to the care of the dying, especially those with tuberculosis and cancer.

Similar facilities began to appear in France, Italy, and the United States, usually organized by religious groups.

-

The modern hospice movement is widely credited to Dame Cicely Saunders, an English nurse, social worker, and physician.

1948–1950s: Working with terminally ill patients, Saunders recognized that medical care often failed to address the emotional, spiritual, and social pain of dying. She introduced the concept of “total pain”—encompassing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering.

1967: Saunders founded St. Christopher’s Hospice in London, the world’s first modern hospice. It combined medical expertise, compassionate nursing, and emotional and spiritual support. It also pioneered the use of opioid medications like morphine for effective pain control. St. Christopher’s became a model replicated worldwide.

-

The idea spread quickly to the U.S. during the late 1960s and 1970s.

1969: Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published On Death and Dying, introducing the now-famous “five stages of grief.” Her work helped spark public conversation about dying and dignity.

1974: The first U.S. hospice opened in Branford, Connecticut, led by Florence Wald, a Yale nursing dean who had studied under Saunders.

1978: The U.S. government published a landmark report calling hospice “the most humane and cost-effective” model for end-of-life care.

1982: The Medicare Hospice Benefit was enacted, providing coverage for hospice services nationwide. This marked a turning point, making hospice accessible to millions of Americans.

-

By the 1980s and 1990s, hospice care had spread across Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and beyond. Each country adapted the model to its own healthcare system and cultural context. Today, hospices and palliative care programs exist in over 120 countries, though access remains uneven.

Key milestones include:

1980s: Growth of pediatric hospice programs.

1990s: Integration of hospice principles into hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies.

2000s onward: Expansion of palliative care as a broader field, extending hospice principles to patients earlier in serious illness, not only at the end of life.

-

Hospice today is both a philosophy and a system of care:

Focused on comfort, dignity, and quality of life rather than cure.

Delivered by interdisciplinary teams: doctors, nurses, social workers, chaplains, counselors, volunteers, and aides.

Provided in homes, inpatient hospice facilities, hospitals, and nursing homes.

Supported by strong evidence that it not only improves quality of life, but often extends life compared to aggressive medical treatment.

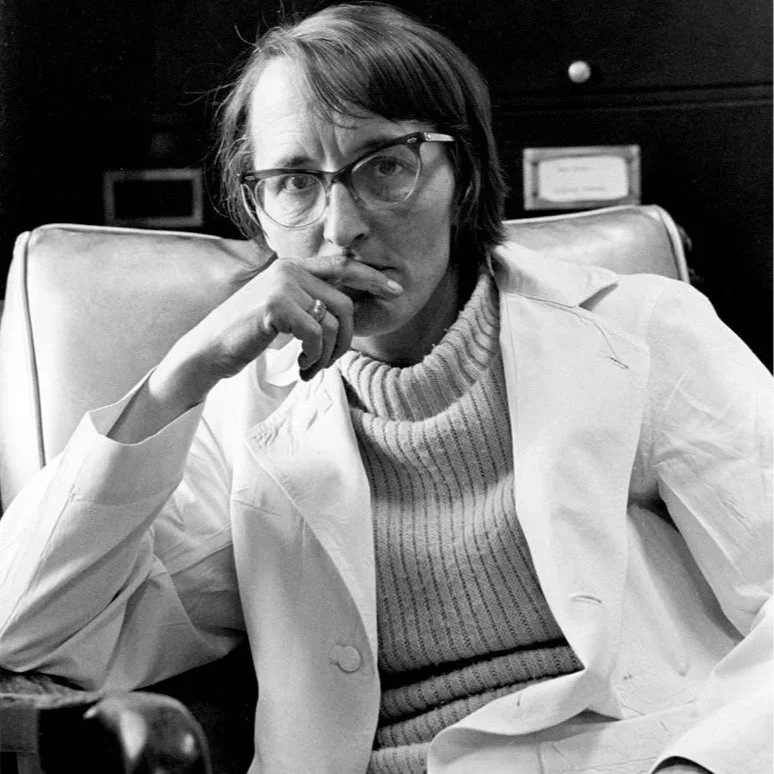

Influential Members of the Hospice Community

Hospice Today: Progress and the Path Ahead

Over the last fifty years, hospice has transformed from a single vision at St. Christopher’s Hospice in London into a worldwide movement. Today, millions of people receive care grounded in hospice principles—comfort, dignity, and quality of life—delivered by interdisciplinary teams in homes, hospitals, nursing facilities, and dedicated inpatient hospices. In the United States, the Medicare Hospice Benefit has ensured access for countless families, while palliative care programs inspired by hospice now reach patients much earlier in the course of serious illness. Globally, more countries than ever before are embracing hospice and palliative care as essential parts of healthcare.

But challenges still remain. Too many people still face the end of life without adequate pain relief, emotional support, or cultural understanding of hospice. Access remains uneven—especially in rural communities, lower-income regions, and across much of the developing world. Misconceptions continue to prevent families from seeking hospice early enough to benefit fully.

The next chapter of hospice will focus on expanding access, equity, and awareness. This includes:

Broadening reach so that all patients—children, adults, and families—have access to care, regardless of geography, income, or culture.

Strengthening education for healthcare professionals and the public to dispel myths and encourage timely referral.

Integrating innovation, from telehealth to community-based models, to meet families where they are.

Advocating globally so pain relief and compassionate end-of-life care are recognized as basic human rights.

Hospice has always been about more than medicine—it is about honoring life’s final chapter with meaning, comfort, and dignity. The progress made so far is remarkable, but the true measure of success will be a future where no one faces the end of life alone, in pain, or without support.